Hardware Memory Models

02 Nov 2024We’ll look at hardware exposing relaxed (non-intuitive) concurrency behaviour to programmers, and methods to get enforce synchronisation there. We’ll mostly talk about the ARM and POWER architectures. Side aim is to motivate the C++ memory model.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Sequential Consistency

- Total Store Ordering (TSO)

- ARM and POWER

- The Message Passing (MP) Litmus Test

- Memory barriers

- Enforcing Order with Dependencies

- Summary

Acknowledgement

All of this article is being taken from A Tutorial Introduction to the ARM and POWER Relaxed Memory Models. I’ve tried to distill the paper for this post to motivate the C++ model, which will be followed up in a later post. Read the paper for much more in depth understanding than I can hope to achieve here.

Sequential Consistency

This is the strongest consistency exposed by a memory model. As articulated by Lamport:

the result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its

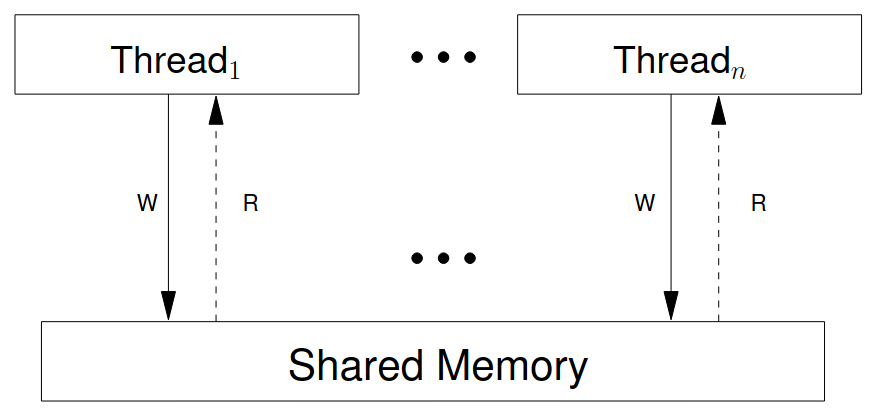

A sequentially consistent machine can modelled as:

Such a machine has two properties:

- There is no local reordering: each thread executes instructions in the program order completing each instruction before starting the next.

- Each write becomes visible to all threads (including the thread doing the write) at the same time

Total Store Ordering (TSO)

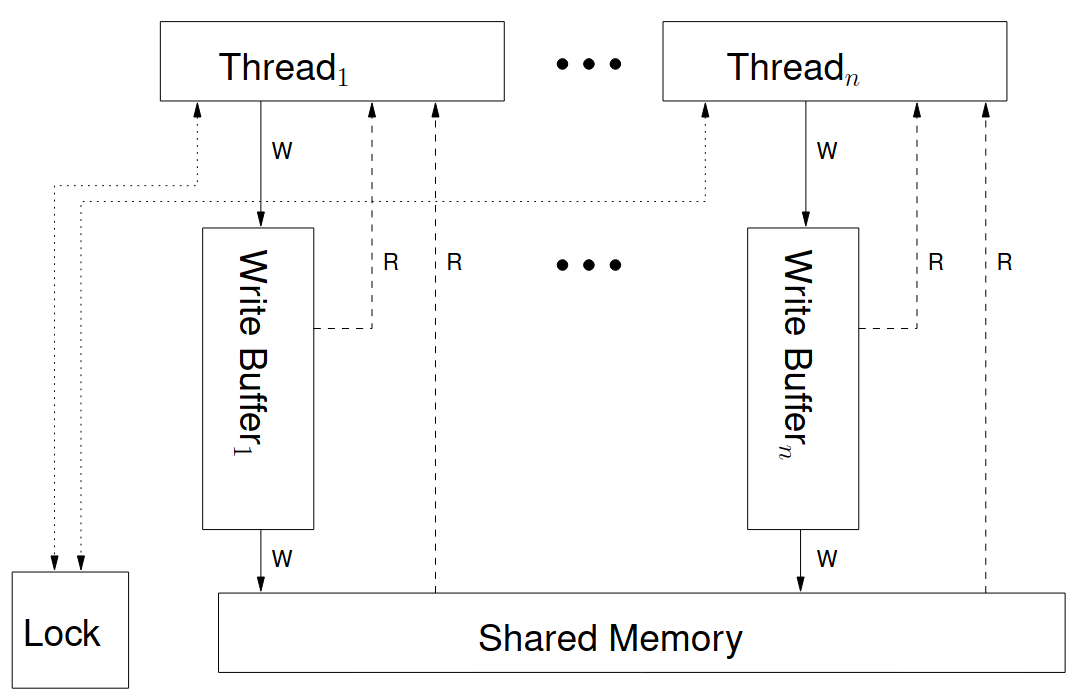

x86 and SPARC architectures are based on the Total Store Ordering (TSO) model. ARM and POWER are much weaker than TSO, as described in sections below.

Each hardware thread writes to a FIFO pending memory writes buffer, thus writes don’t block on flushing to the main memory. Moreover, they read from the memory buffer if there is a pending write present for the memory address. Thus a thread always reads its own writes.

Note that a write becomes visible to all other threads simultaneously. This behaviour of a write becoming visible to all other threads simultaneously is referred to as multi-copy atomicity

ARM and POWER

ARM and IBM Power have considerably more relaxed memory models. In absence of memory barriers or dependency guarantees:

- Threads can perform reads and writes out-of-order, or even speculatively.

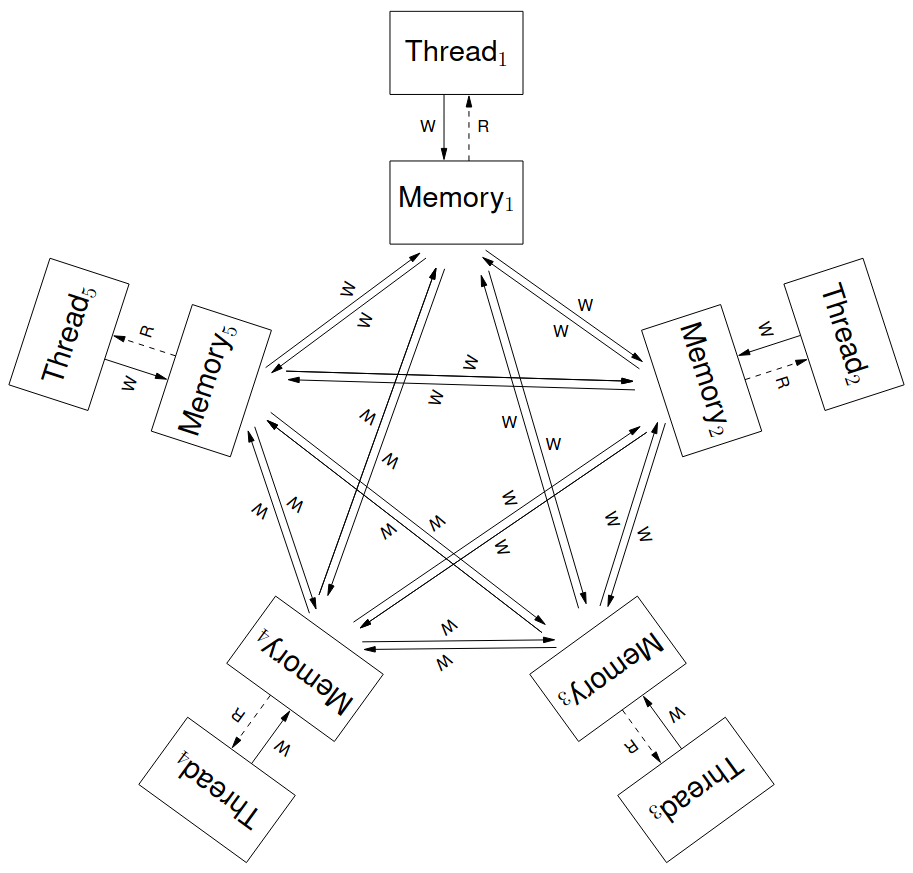

- The memory system does not guarantee that a write becomes visible to all other threads at the same point => these architectures are not multi-copy atomic.

Note that first point can make sense in order to keep the processor pipeline full. The second point makes sense thinking that a group of processors can share L2 cache while another group can have a different L2 cache. So a read being flushed to the L2 cache means it’s visible to one group and not the other.

To think about a non-multiple-copy-atomic mechanism, we can think of each thread having its own copy of memory. A write by one thread may propagate to other threads in any order, and the propagation for different addresses can be interleaved arbitrarily.

For thread-local out-of-order (and speculative) execution, we can think of each thread, at any point of time, as having a tree of committed and in-flight instruction instances. Newly fetched instructions become in-flight, and later, subject to appropriate preconditions, can be committed.

In the below diagram, instruction instances {i_1, ..., i_13} are shown with program-order relation among them. The boxed instructions have been committed whereas the others are in-flight.

Note that committed instructions are not necessarily contiguous. Instructions from both branches of a conditional are also pre-fetched. The un-taken paths are discarded, and instructions following an uncommitted branch remain uncommitted.

Read instructions can be satisfied as soon as the address is known, binding its value to one received from local memory. However they can be restarted or aborted, until the read is committed. Write Instructions can be satisfied once the write and value become determined, afterwards the write can be committed.

The Message Passing (MP) Litmus Test

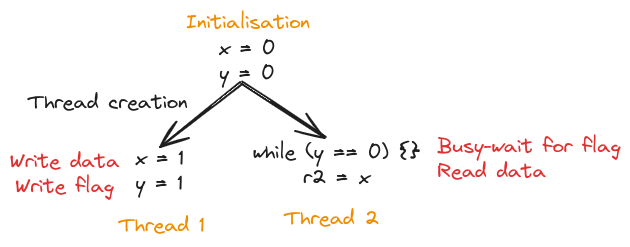

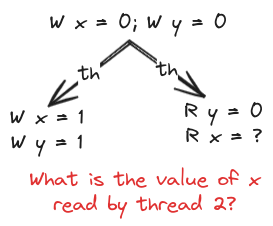

Consider the program in the below figure, having 2 threads writing to two variables x and y. We want to see if the r2 register can get the value 0, i.e. can thread 2 read x as 0.

This is a common pattern of passing data between threads. One thread writes the data and then sets a flag variable. The other thread waits for the flag to be set appropriately and then proceeds to read the data. We want to see if this pattern works in a memory model. This is a Litmus Test: a test to find out about the properties of a memory model.

Note that we can simplify the above diagram removing the while loop. We can just take the case where thread 2 reads x as 1, and then proceeds. Also, we keep it implicit that different vertical lines of codes mean different threads and use th for thread creation. Writes are denoted by W and Reads are denoted by R. Using these conventions, the above diagram simplifies to:

Outcomes

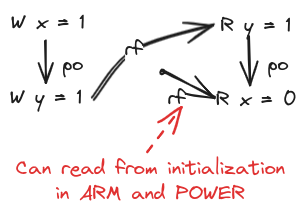

Thread 2 can’t read x as 0 on x86 and SPARC. In TSO, a hardware thread’s FIFO buffer is flushed to the memory together, so a later write (to y) becoming visible means that the earlier write (to x) will also be visible. However, R x = 0 is possible on ARM and POWER. This can be due to reordering of writes or reordering of reads that is possible in these architectures.

Here, we again simplify the diagrams. We’ll assume all variables implicitly initialised to 0. Arrows labelled po denote program order and rf denotes reads from. Reads-from relation is from a write to a read of the same variable such that there is no intervening write between them. A read from an initialisation is denoted as an arrow from a point.

Memory barriers

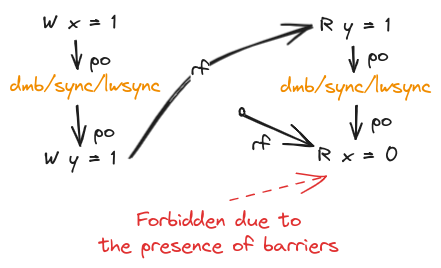

To allow Message Passing to work, we need to eliminate out-of-order executions. This is done adding a strong memory barrier between the two writes on the first thread and the two reads on the second thread. These are ARM’s dmb and POWER’s sync/hwsync instructions. There is a lightweight barrier lwsync available on POWER which also does the job.

R x = 0 by the second thread is forbidden due to the synchronization provided by the barriers. Let’s look at the four cases of having a read or write before and after a barrier to see their properties. Note that unless mentioned otherwise, the statement is true for all of dmb/sync/lwsync.

- RR: Barrier will ensure the reads are satisfied in program order, and are also committed in program order

- RW: Barrier will ensure the read is satisfied and committed before the write can be committed, and hence before the write can propagate and be visible to any other thread

- WW: Here the behaviour differs between

dmb/syncandlwsync:dmb/syncwill ensure that the first write is committed and has propagated to all other threads before the second write is committedlwsyncwill ensure that for any particular thread, the first write propagates to that thread before the second does

- WR: Here there is a difference in behaviour too:

dmb/syncwill ensure the write is committed and has propagated to all other threads before the read is satisfiedlwsyncwill ensure the write is committed before the read is satisfied, but lets the read be satisfied before the write has propagated to any other thread.

Note that our Message Passing example has WW and RR accesses separated by barriers. WW property ensures the first write propagates before the second one does and RR ensures that first read is satisfied before the second one. It’s easy to work out why the second thread reading x = 0 is not allowed.

Enforcing Order with Dependencies

The memory barriers are stronger than necessary for the Message Passing example. We can do prohibit undesired behaviour with dependencies.

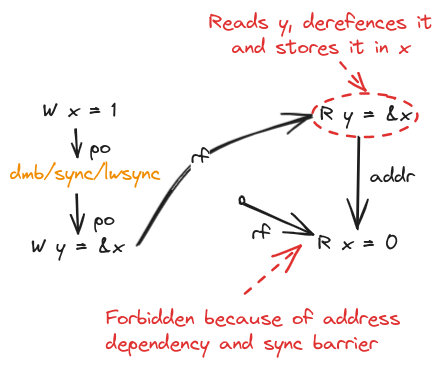

Address Dependencies

There is an address dependency from a read instruction to a program-order-later read or write instruction when the value read by the first read is used to compute the address used for the second.

If we add an address dependency between the reads in Message Passing, we don’t have to add any barriers. We’ll still have to add barriers for the writing thread so writes are not committed/propagated out of order.

C11/C++11 consume: This preserved address dependency is what is made available in C++11 memory model by read-consume atomic operations. Note that as of C++17, read-consume is temporarily discouraged

Address Dependencies can also be added articially, called Artifical Dependencies. The following example used on the second thread of Message Passing can be used as a programming idiom:

r1 = y

r3 = (r1 xor r1)

r2 = *(&x + r3)

Observe that r3 will always be 0, and r2 will just become equal to x. This kind of instruction will be removed by optimizers in most compilers, so this probably only makes sense when writing in assembly directly.

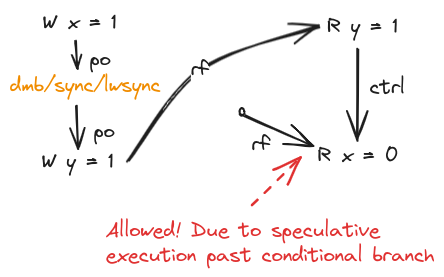

Control Dependencies

A control dependency form a read to program-order-later read or write instruction, where the value read by the first read is used to compute the condition of a conditional branch that is program-order-before the second read or write.

A control branch from a read to read has little effect as ARM and POWER processors can speculatively execute past the conditional branch, satisfying the second read. The first read, conditional branch and second read are then committed in that order with the values.

We can add a control dependency like so:

r1 = y

if (r1 == r1) {}

r2 = x

NOTE: The existence of the control dependency simply relies on the fact that the value read is used in the computation of the condition, not on whether the value of the condition would be changed if a different value were read.

Adding such a control dependency is not enough to restrict relaxed behaviour in our running example:

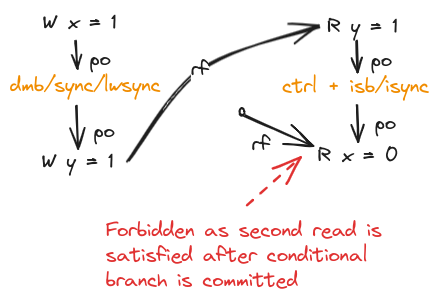

Control-isb/isync Dependencies

To strengthen a read-to-read control dependency, we can add a ISB(ARM) or isync(POWER) instruction between the conditional branch and the second read. This prevents the second read from being satisfied before the conditional branch is committed.

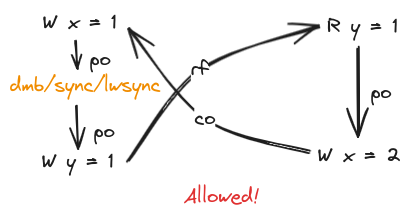

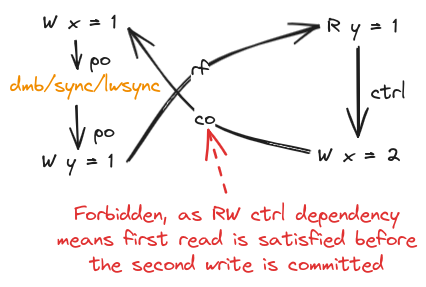

Control Dependencies from a Read to a Write

A control dependency from a read to a write has some force: the write cannot be seen by any other thread until the branch is committed, and hence util the value of the first read is fixed.

We use a variation of MP, known as S, where read of x in the second thread is replaced by a write to x. Here, we think about the order of writes to x which is called the coherence-after relation (or the memory-order relation). A write a to a variable x is coherence-after and write b to x when any other thread cannot observe write b happening before write a. This relationship is drawn with a co edge.

Interestingly, observe the cycle formed with po, rf and co edges. This means there’s no causal relationship between all the arrows, since of course we can’t go backwards in time.

By adding a control dependency using a simple if (r1 == r1) {} as illustrated in the previous section, the relaxed behaviour is forbidden.

Data Dependencies from a Read to a Write

A data dependency is from a read to a program-order-later write where value read is used to compute the value written. The effect is similar to other dependencies: it prevents the write being committed until the value of the read is fixed when the read is committed.

Summary

We started with a Sequentially Consistent abstract machine, then weakened it to a Total Store Ordering (TSO) machine that has Store Buffers. This is the model used by x86 and SPARC. Further weaking gave up the abstract machines for ARM & POWER which do speculative reads/writes and are not multi-copy atomic.

To add synchronization to our ARM & POWER code, we looked at memory barriers dmb/sync and POWER’s lightweight lwsync. We also looked at multiple types of dependencies that can be used to enforce ordering.